What would you guess small teams, competition of ideas, social dynamics, and enhanced advancement of science have in common? If you had just seen two of the keynote talks at ISMB 2025 in Liverpool you might guess: Alpha-fold and Agentic AI.

John Jumper (Director at Google DeepMind) gave a keynote summarizing the development path from AlphaFold 1 to AlphaFold 3. It turned out to be mostly a series of small improvements coming from many different members of a small and agile team with the freedom to explore half-baked ideas on a whim. He was very specific about multiple brains on a team being more powerful than individuals working in isolation. During the question/answer session someone asked him the typical academic junior scientist’s lament: When industry can develop tools as impactful as AlphaFold, how are academics supposed to compete? He had a curious answer I thought was relevant for the Institute where I work. He’s worked in academia and industry, and mentioned that the AlphaFold team, and teams like it, small teams of around ten or a dozen people working together on some project are very powerful. Yet you tend not to see these little social structures in academia and he didn’t really understand why. He didn’t think there was anything fundamentally industry specific about the way his work unfolded that couldn’t exist in academia. One of the strengths of the Institute where I work is the degree to which collaboration on projects occurs across both PI and technology groups. I feel like there’s something to explore there.

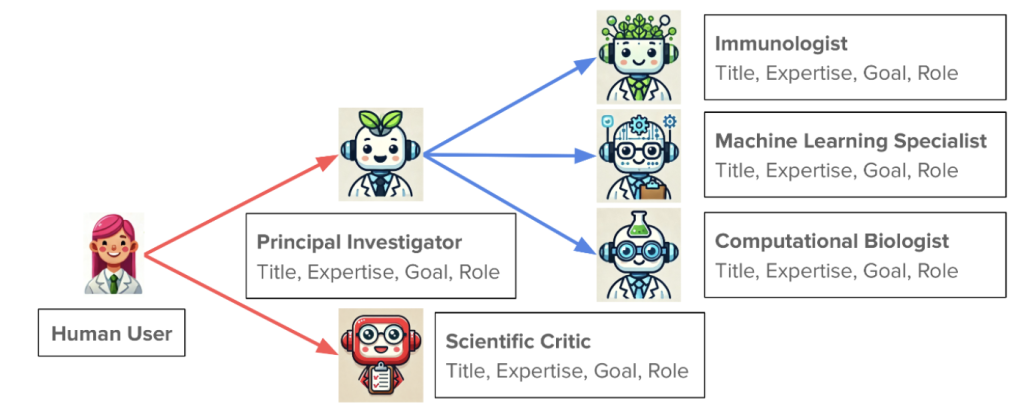

The second talk was from James Zou at Stanford. His talk puts a research group in everyone’s pocket. More specifically, Agentic AI is at your fingertips and you can start your own virtual lab to suggest experiments you can do in the real world, or just comb over and analyze existing data sets for novel findings to new questions. Here’s how it works.

Your lab would consist of a team of independent AI agents, each with specific roles or specialties. For instance you would have a PI, a protein structure specialist, a machine learning specialist, a computational biologist, an expert on bacterial physiology, and of course a critic. You would instruct this team to solve some real world open scientific problem. For instance: find protein interactions that can modulate growth rate in response to a set of peptide candidates. The team would then have meetings to come up with strategies. You can see the results of these meetings as they occur using human readable language formats, and the virtual PI can even give you executive summaries of how the meetings are going. At the end they produce a defensible research plan that can be executed in the lab.

He demonstrated the success of the approach by instructing a virtual research team to design nanobody binders to recent variants of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and then tested them in the lab and some of them actually bound!

If this isn’t odd enough, what struck me was the extent to which the procedure mimicked aspects of humanity. The agent meetings had the same properties as human meetings. There were social dynamics. Some agents spoke more than others. Disagreements occurred and were resolved. Importantly, the idea of separating the task among independent entities that could interact was vitally important. This allowed for independent approaches and relied on a competition of ideas, rather than simply one big computer program that does all the “thinking” on its own. Indeed, since it was a computational setup, one could create several instances of a virtual lab and run them in parallel, and he mentioned that different strategies emerge.

The last thing that seemed immediately promising using this approach to research was the evaluation and exploration of existing data sets. The whole point of FAIR data is that large genomic data sets contain more information than is usually extracted for a given project, and by putting them in an accessible repository they can be used for other analyses, or to reproduce the results reported in a given paper. These can easily be a resource for your virtual agent research group! He showed examples of unleashing virtual research groups on existing data sets and they made various novel findings that were not reported in the original publications.

It was both chilling and exciting to see new ways in which research can be done. I think AI is changing the way people approach projects, and this struck me as proof positive that impacts are coming we can’t yet imagine. If people are walking around with research teams in their pockets, maybe they can add a communication specialist to the team so that the virtual labs can talk to each other and alert their human users of when they should talk to each other. We can’t let the virtual agents get better at sharing ideas than us! 🙂